by Swami B.G. Narasingha

'Purī – Cultural Cataracts. A British View of India' was written by Swami B.G. Narasingha on 1990 for Clarion Call magazine, Vol.3 issue 1. In this article, Swami Narasingha gives a history of the Jagannātha Temple in Purī, Orissa, as well as a description of the Ratha Yātrā festival and how the British perceived it.

“Juggernaut: a massive, inexorable force that crushes everything in its path.”—Oxford Dictionary

Spiritual and intellectual efforts of hundreds of millions of people over millennia have graced India with a rich and complex culture—a culture whose subtlety knows no rival. During the last three centuries the attempts of most Westerners to penetrate the spiritual dimension of Indian culture has at best been doomed to superficiality.

Although some sincere seekers of truth from outside India’s borders have succeeded in their pursuit of Indian spirituality (and this is increasing as time goes on), still, the vast majority of the Western world remains caught in the slumber of misconception, much of which can be traced to an insufficient fund of knowledge and misinformation. Without the benefit of a preliminary briefing or education in Indian spirituality, a newcomer to India is certainly at a decided disadvantage, and is apt to view things according to his or her own cultural or religious biases. Of course this cultural cataract has marred many attempts to understand another’s culture, yet the British view of India is perhaps one of the most vivid examples of misunderstanding that continues to take its toll today, some 40 years after Indian independence. Thus perhaps the richest spiritual heritage on Earth has been relegated to obscurity in modern times.

After a visit to India, Mark Twain once said, “East is East and West is West and ne’er the twain shall meet.” This is certainly true on the physical plane, but the very nature of spirit is that it is neither Eastern or Western. India has, as her trademark, demonstrated an exemplary attitude of religious tolerance for many centuries, accommodating a vast number of different religious traditions within her borders: Jewish, Christian, Zoroastrian, Muslim, and Hindu, among others, thus demonstrating that religious harmony does not depend on geographical considerations.

How the basic misconceptions about Indian spirituality first developed vividly comes to light when we examine history between 1690 and 1947, during which time Great Britain occupied India.

The British began their conquest of India from Calcutta, where they established the East India Company—a business venture that was destined to rule India with an iron fist for almost 250 years. When the Britishers returned to their motherland, they depicted India as a barbaric, uncivilized country filled with polytheism, mythology, and idolatry. The scene they painted portrayed India as a country of primitive worshipers bowed down before a ghastly statue of some god or goddess. To them this represented one of the most hideous examples of human degradation, one of those horrors of ignorance which the British had long left behind. The British summed up India as a hodgepodge of heathenistic superstitions. This attitude toward India and her spirituality was shared by just about every Britisher in India and at home, from the King and Queen of England down to the desk clerk at the East India Company in Calcutta. They felt nothing of value could be gained from the “primitive Hindus” except their abundance of gold and jewels. However, in actuality the British had stumbled upon the oldest and most civilized society—in terms of spiritual culture—in the world. Sadly, the British view of India was to become the prominent world view of India.

During the early days of imperial rule in India, the British received some of their first impressions of India’s spiritual culture via their encounters in the holy city of Jagannātha Purī—encounters which plunged the British deep into severe cultural shock.

Jagannātha Purī is located on the east coast of the Indian sub-continent in the tropical state of Orissa, about 310 miles south of Calcutta. It has been a holy place of pilgrimage for devout Hindus since ancient times. The city is shaped like the silhouette of a conch-shell. The shape of the conch-shell bears the spiritual significance of Jagannātha Purī being the abode of the Godhead, Viṣṇu, who carries a conch-shell as part of his eternal paraphernalia. In the centre of the conch-shell silhouette there is a portion of raised ground called Nīlagiri or “the blue hill.” On the crest of Nīlagiri stands an imposing temple complex dedicated to Viṣṇu as Jagannātha, “the Maintainer of the Universe.” In Sanskrit jagat means the universe, and nātha means the maintainer.

It has been a standard practice in India since ancient times to develop a city or village around a central holy shrine. Thus the temple of Jagannātha is established at the centre of Jagannātha Purī. Situating the temple at the centre of the city had a twofold justification: apparent and transcendental. The apparent reason was a practical one; the temple being in the centre of the community provided easy access for community gatherings. The transcendental reason was a philosophical one: the people of ancient India conceived of the Godhead as being at the centre of the universe and at the centre of all activities in the universe. Thus the temple being at the centre of the community acted as a reminder that human life is ultimately successful when everything is dedicated to the Godhead at the nucleus.

The proper name of the temple in Jagannātha Purī is Śrī Mandira, and according to the palm leaf chronicles therein, the temple has existed for a very long time. The present temple structure, built in the twelfth century by King Chodagaṅgā Deva, soars 215 feet into the air and spans an area of more than 428,000 square feet. Surrounding this massive structure is a stone wall 20 feet high with four large gates: the elephant gate, the lion gate, the horse gate, and the tiger gate. These gates face north, east, south, and west respectively; the temple itself faces east as is customary in Indian temple construction.

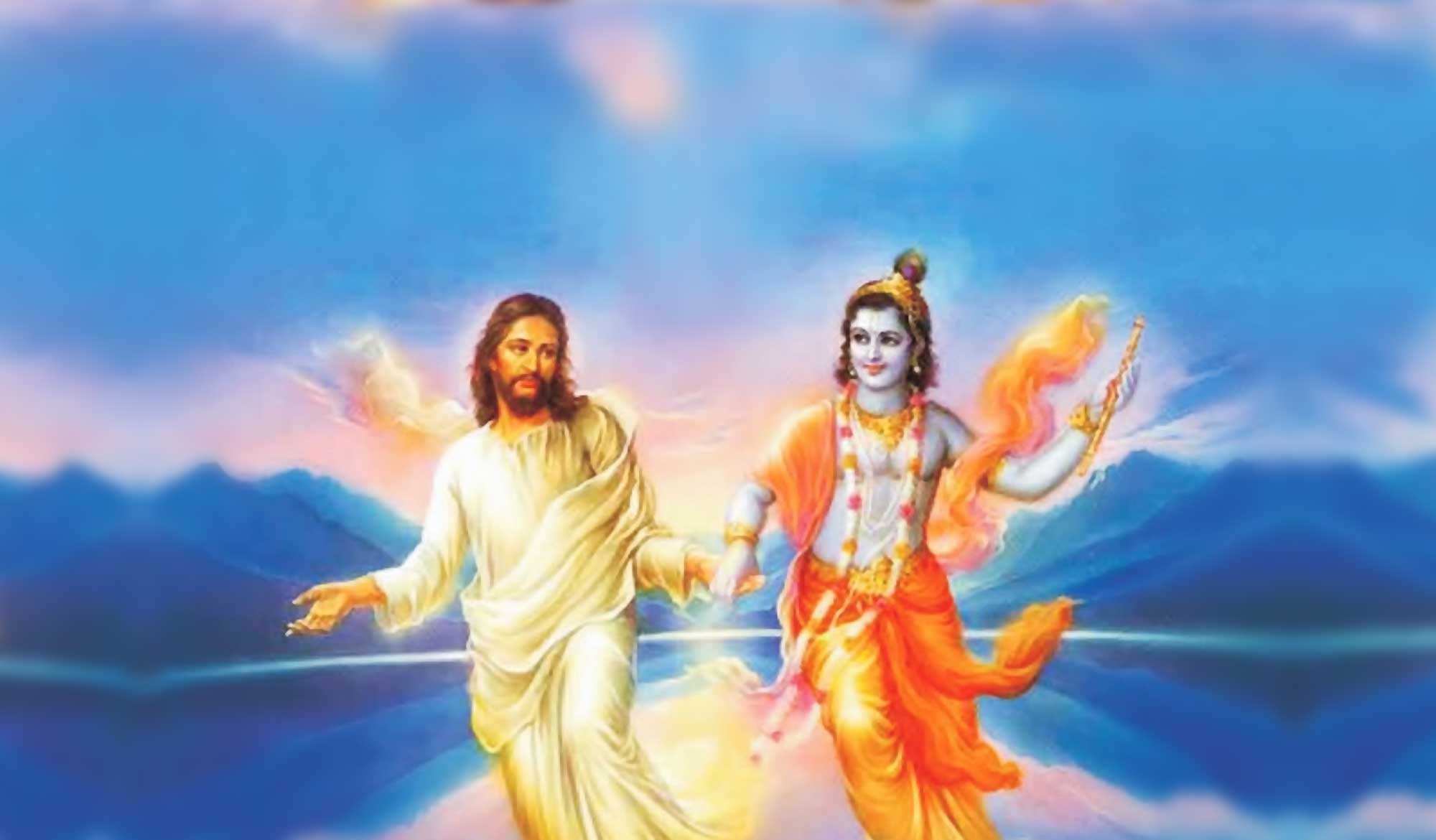

Within the main compound of Śrī Mandira there are over one hundred shrines of lesser importance which are committed to the demigods in charge of universal affairs or the sub-controllers of the universe. In the midst of these lesser shrines is the main temple hall called the baḍa-deula, in which resides the predominating Deity of the temple, Śrī Jagannātha. The Deity’s eyes are large and round like the lotus flower, his complexion is blackish, and his nature is all-merciful to his devotees.

Śrī Mandira is one of the best examples of spiritual culture found anywhere in India, past or present. The standards of worshiping the Deity have been going on for many centuries without interruption in the grandest style imaginable. Fifty-four separate offerings of vegetarian food are prepared daily and offered to Jagannātha. For the preparation of these offerings, an exceptionally large kitchen called the bhoga-maṇḍapa is required. This happens to be the largest kitchen in Asia, and it employs 650 people as cooks and assistants.

It is believed that the food offered to Jagannātha becomes prasādam, ;the mercy of God,’ which when eaten, destroys one’s karmic reactions and thus helps to Purify one’s existence. Over 50,000 people take prasādam at the Jagannātha temple every day.

Before entering the main shrine of the Deity there is a finely crafted hall with many pillars called the nāṭa-maṇḍapa or ‘dancing hall,’ and pilgrims, devotees, and worshipers of Jagannātha often perform dancing and singing there for the pleasure of Jagannātha. Previous to British rule, the Jagannātha temple maintained several hundred deva-dāsīs, or maidservants of Jagannātha, who would frequently perform dance and drama in the nāṭa-maṇḍapa. These deva-dāsīs were considered the wives of the Deity, and thus they did not marry any man of the mortal world. The system of the deva-dāsīs was a voluntary one, and never involved any kind of slavery, as was misconstrued by the British overlords during their rule in India.

In the baḍa-deula main hall of Śrī Mandira, Jagannātha rests on a five-foot-high stand called the ratna-siṁhāsana, the jewelled throne. The Deity itself is also about five feet tall. To the right of Jagannātha are two other thrones: one for Subhadrā, the sister of Jagannātha, and one for Baladeva, the older brother of Jagannātha.

According to the worshipers of Jagannātha, Godhead is never alone. He (in this case it is he, the male aspect of Godhead, Puruṣa) is eternally engaged in transcendental pastimes via the manifestation of his own internal energies. These pastimes are said to exist eternally on the absolute plane of reality. Godhead, they say, is complete in his existence, yet for the pleasure of himself and his loving servants, he creates a world of transcendental variegatedness called the paravyoma, the spiritual sky. Subhadrā and Baladeva are said to exist in the spiritual sky as members of the divine family and are thus worshiped along with Jagannātha at Śrī Mandira.

Six times a day beginning at 4 A.M. and ending at 9 P.M., the main hall is open to the devotees for viewing the Deity. This is called darśana. During these times the worship of Jagannātha is enthusiastically performed and the devotees become absorbed in ecstatic rapture.

How the Deity of Jagannātha appeared and came to be worshiped at Jagannātha Purī is an interesting story which one can learn from any of the temple priests: A millennia ago there was a pious king named Indradyumna who ruled the province of Mālava, extending from Jagannātha Purī to the southern tip of India. King Indradyumna was a spiritual-minded man, and as such he always favoured the association of sages and saintly persons. One day while listening to the sages, the king heard that the ultimate realization is that of the personal form of Godhead. From that day on the king cultivated a desire to see the form of Godhead in the core of his heart. Knowing that such a desire may take many lifetimes to perfect, the king continued to rule his kingdom and to associate with the saints and sages.

One night, King Indradyumna had a dream that Viṣṇu came to him. During this dream, Visnu said that the king would find a wooden log at the seashore and that he should take this special log and get it carved into a Deity according to the direction found in the Śilpa-śāstra, the authorized scripture which governs such things. When the king awoke from his dream he was exceedingly happy and went directly to the seashore, where he found a very large log lying on the beach.

King Indradyumna’s men carried the heavy log back to the palace, and the king ordered his carpenters to begin the wood carving. However, the wood was so hard that whoever tried to carve it simply broke his tools. The king was very perplexed and thus he took rest for the night.

The next day, Visvakarmā, the architect of the celestial world, came to see King Indradyumna. Viśvakarmā informed the king that the log which he had found at the seashore was dāru-brahman or divine wood. Viśvakarmā said that it would not be possible for any mortal to carve this wood, but that he himself would do it if the king desired.

As Viśvakarmā prepared to do his work, he informed King Indradyumna that there was one stipulation: no one should be allowed to observe the work of carving until everything was complete. Viśvakarmā said that if his meditation were disturbed, he would immediately abandon the king and return to the celestial world. The king agreed.

Many days passed and King Indradyumna patiently waited while Viśvakarmā carved away in a secluded chamber. Unfortunately, the king’s wife Guṇḍicā was not so patient as her husband; Guṇḍicā repeatedly urged her husband to take a peek at the progress. Remembering his agreement with Viśvakarmā, King Indradyumna was naturally reluctant. Then one day, the noise of hammering and chiseling stopped and not even the slightest sound could be heard coming from Viśvakarmā’s studio. The suspense of silence pushed the king to the edge of his patience and he and Guṇḍicā slowly opened the door to the studio. Before the door was halfway open, Viśvakarmā vanished from sight, leaving his tools on the floor and his work unfinished.

King Indradyumna was mortified at this turn of events and his heart felt heavily burdened. In order to expiate for the interruption and incomplete work, the king decided to fast until death. While fasting he again had a dream in which Viṣṇu told him that the incomplete forms of the Deities were in fact perfectly worshipable forms. The so-called incompleteness, he said, represented bodily transformations resulting from intense love in separation, a particular ecstatic mood known as vipralambha. In the case of Jagannātha, it was the Puruṣa’s longing for his female aspect prakṛti in intimacy. Overjoyed by these instructions, King Indradyumna arranged for the building of a beautiful temple and for the worship of the Deity which continues even to this day.

The British regarded all these stories about the appearance of Jagannātha as mythology and never took them seriously. Neither did the British ever enter the temple to observe the loving ecstasy of the devotees who worship Jagannātha. They assumed the whole affair to be idol worship. However, there was one occasion when the British did get the opportunity to see Jagannātha face to face and to witness the great devotion of his devotees. Every year the temple of Jagannātha holds a marvellous festival called Ratha Yātrā. It appears from the temple records that this festival is the oldest regularly performed spiritual function in human society.

The Ratha Yātrā is held annually in mid-July and lasts for several days. Preparations begin months before with the construction of three exceptionally large chariots or rathas. To build the large chariots, vast amounts of wood are required, which is brought to the main road in front of the temple and placed in stacks. Day and night workers paint the individual parts of the chariot and begin to assemble them one by one; soon the shape of the chariots becomes manifest. Each chariot towers three stories high while standing on sixteen wheels. When the super-structure is complete, the upper portion of each chariot is covered with a brightly coloured canopy of red, yellow, black, and green silk. The wheels are eight feet in diameter and a slightly sagging hand rail encloses the upper deck of the chariot. On top of the canopy there is an impressive gold spire flanked by two green parrots carved in wood and a yellow silk flag.

Pilgrims are astonished to see the beautiful decorations of the chariots. The chariots have a celestial beauty and appear as high as a great mountain. The decorations include bright mirrors, white whisks, pictures, sculptures, brass bells, and iron gongs. When the chariots are completed, thousands and thousands of pilgrims begin to arrive from all over India. On the actual day of the festival, over one million people are present, including some of the top ministers in the Indian government, generals from the army, and occasionally even the prime minister. At the lion gate everyone gathers with an intense eagerness as they wait for Jagannātha to be brought from the temple and placed on his chariot. Suddenly, heralded by the blowing of conch-shells, the smiling face of Jagannātha appears in the doorway of the temple. The crowd stands, jumps, and shouts a welcome praise to the Lord of the universe, “Jagannātha ki jaya! Jagannātha ki jaya! Jagannātha ki jaya!”

As the Deity emerges from the temple he is supported on both sides by strongly built men called Dayitās. A series of sturdy cotton pillows called tulīs are spread out from the temple door to the chariot, and the heavy Deity of Jagannātha is carried from one pillow-like pad to the next. Moving from pillow to pillow with a graceful swaying motion, Jagannātha gradually ascends his chariot.

The Dayitās say,”Jagannātha is the maintainer of the whole universe. Therefore, who can carry him from one place to the next? Jagannātha moves by his personal will just to perform his pastimes.” This first aspect of the festival where Jagannātha mounts his chariot is called the Pāṇḍu-vijaya and takes about one hour.

The Deities of Subhadrā and Baladeva are similarly transported to their chariots as the parade is about to begin. Joining Jagannātha on his chariot are dozens of enthusiastic servants and devotees. Surrounding the chariots are devotees from Bengal and Orissa who begin to sing melodious devotional songs accompanied by the music of clay drums and hand cymbals. A minister of the government then comes forward and sweeps the road in front of the chariots with a gold and silver broom. Then sandalwood-scented water is sprinkled on the freshly swept road. Seeing the highly posted minister engaged in menial service to the Deity, the people become very happy.

Four long, extra-heavy ropes are attached to the front of each chariot and extended into the crowd of people. Taking the ropes in hand, a hundred or more people on each rope, everyone awaits the signal from the chariot driver to begin to pull. A whistle sounds one long blast, the rope tightens, and the chariot begins to roll. The huge wooden wheels wobble from side to side as they squeak and turn on their heavy wooden axles. The chariot pullers, called Gauḍas, pull with great happiness. The chariot sometimes moves quickly, sometimes slowly. Mysteriously the chariots sometimes come to a complete stop even though everyone is pulling very hard. It appears that the chariots are moving by the will of Jagannātha. Making their way along a stretch of road for about three miles, the chariots arrive in front of the Guṇḍicā temple, where they remain for some days and then return to the Jagannātha temple in a similar manner.

There is a profound spiritual meaning behind the Ratha Yātrā which the great sages and devotees of Jagannātha have described thus:

“The worship of Jagannātha is generally conducted on a grand scale of awe and reverence wherein his devotees see and revere him as the Supreme Godhead. This mood of awe and reverence, however, is not as pleasing to Jagannātha as the mood of spontaneous love of God exhibited by his most confidential devotees the gopīs, the milkmaids of Vṛndāvana. In the mood of awe and reverence, Jagannātha is always found in the company of Lakṣmī, the goddess of fortune. But sometimes Jagannātha remembers the intimate loving affairs between himself and the gopīs, and thus he is overwhelmed with feelings of separation and desires to return to Vṛndāvana. Jagannātha then leaves his temple and mounts his chariot to go to Vṛndāvana and meet with the gopīs. As Jagannātha sees the white stretch of sandy road in front of his chariot with beautiful gardens on both sides, he is reminded of the Yamunā River and the groves of Vrndavana where he sported with his gopīs. Jagannātha’s mind becomes filled with pleasure at these thoughts and he smiles intensely.”

The esoteric meaning of the Ratha Yātrā combined with the actual beauty of the event have inspired many devotees to compile excellent songs and poetry in praise of Jagannātha. Famous in Jagannātha Purī are the beautiful verses known as Jagannāthāṣṭakam, which are vibrated from the lips of thousands of pilgrims during the festival:

“Sometimes in great happiness Jagannātha, with his flute, makes a loud concert in the groves on the banks of the Yamuna. He is like a bumblebee who tastes the beautiful faces of the cowherd damsels of Vṛndāvana, and his lotus feet are worshiped by great personalities such as Lakṣmī, Śiva, Brahmā, Indra, and Gaṇeśa. May that Jagannātha be the object of my vision.”

“In his left hand Jagannātha holds a flute. On his head he wears a peacock’s feather, and on his hips he wears fine yellow silken cloth. Out of the corners of his eyes he bestows sidelong glances upon his loving devotees, and he always reveals himself through his pastimes in his divine abode of Vrndavana. May Jagannātha be the object of my vision.”

“Jagannātha is an ocean of mercy and he is beautiful like a row of blackish rain clouds. He is the storehouse of bliss for Lakṣmī, the goddess of fortune, and Sarasvatī, the goddess of learning, and his face is like a spotless, full-blown lotus. He is worshiped by the best of demigods and sages, and his glories are sung by the Upaniṣads. May that Jagannātha be the object of my vision.”

“When Jagannātha is on his chariot and is moving along the road, at every step there is a loud presentation of prayers and songs chanted by large numbers of brāhmaṇas (priests). Hearing their hymns, Jagannātha is very favourably disposed towards them. He is the ocean of mercy and the true friend of all the worlds. May that Jagannātha be the object of my vision.”

Unfortunately, the British did not have the same visions of Jagannātha as did his devotees. Not only did they see something less beautiful and charming but they saw something quite ghastly. Perhaps it was a projection of their own inner natures since it was they who had come to India as conquerors and not as seekers of truth.

The British described Jagannātha as “a frightful visage painted black, with a distended mouth of bloody horror.” Seeing the grand procession of the Ratha Yātrā, the British experienced further disdain and coined the term ‘juggernaut.’ This word gradually found its way into the Oxford Dictionary with the meaning “a massive, inexorable force that crushes everything in its path.” It could hardly be expected that the British should have immediately fallen in love with Jagannātha or worshiped him, but at least they could have investigated the meaning and philosophy behind him. Instead they maligned Jagannātha to the world as ‘a horrible, bloodthirsty idol.’ Lamentable as it was, the British view of India spread throughout the world, and thus for centuries the real beauty of India’s spiritual conceptions remained undiscovered.

But fortunately, we in the Western world are gradually maturing culturally, and are becoming more open-minded and receptive than ever before to learning what India has to offer the West. And Jagannātha’s big eyes are still beaming, and his wide smile still invites all people to come to Jagannātha Purī every year to enjoy the spiritual bliss of the Ratha Yātrā. I have seen this festival with my own eyes, and I doubt that I will ever experience anything quite as prodigious and jubilant in my life.

More Articles by Swami B.G. Narasingha

The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus Christ

The article, “The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus Christ” was written by Śrīla Narasiṅgha Mahārāja under the pseudonym of ‘Pradeep Sharma’ in 2007. This article was in response to various parties begging the question about Jesus being a devotee of Kṛṣṇa and citing a dubious work called the ‘Aquarian Gospel’ as evidence.

Meditation Techniques and the Holy Name

'Meditation Techniques and the Holy Name' was written by Swami Narasingha in October 2006. Narasingha Maharaja discusses the age-old problem of distraction during japa, and gives advice based upon Sanātana Gosvāmī and Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura on how to combat this.

The Burning Cross – Part 2

In ‘The Burning Cross - Part 2’, Śrīla Narasiṅgha Mahārāja, under the pen name of Pradeep Sharma, discusses the Goan Inquisition, how the Christians viewed Lord Jagannātha in Purī, and the thoughts of the Founding Fathers of the Unites States about Christianity.