by Swami B.G. Narasingha

‘Śaṅkarācārya - The Incarnation of Śīva’ was written by Swami B.G. Narasingha in 1990 for Clarion Call magazine. In this biographical article, Swami Narasingha narrates the life of the great founder of Advaita Vedānta, Ādi Śaṅkarācārya. This article was later published in the book, 'Evolution of Theism.'

“I am neither void nor nonexistence. I am the one, Brahman.”

Ours is an age of inquiry into the secrets of the cosmos and life itself. As an intelligent people we crave to know what is beyond. We study the nature of things in this world to further our understanding of who we are and where we came from. We fill our library shelves with volumes of books so that future generations may share in the wealth of our discoveries. We do all these things in the name of science and the advancement of knowledge. But we are not the first people to inquire about the mysteries of life. In fact, many great civilisations before ours have penetrated deep into the unknown. One such era in bygone days was that of Śaṅkaracārya, who pioneered a paradigm of enlightened thought, the dawning of Impersonal Brahman.

During the eighth century A.D., when Śaṅkaracārya appeared in India, the authority of the Vedas, which guide humanity toward progressive immortality, had been greatly minimised by the prevailing influence of Buddhist thought. At the time most of India’s philosophers, in pursuance of the teaching of Buddha’s śūnyavāda philosophy of negative existence or prakṛti-nirvāṇa, had renounced the Vedic conception of īśvara (the Absolute Truth) and jīva (the eternal spark of the same). Under the patronage of powerful emperors like Aśoka (243 B.C.), Buddhism had spread throughout the length and breadth of India. By dint of his vast learning and his ability to defeat opposing philosophies, in philosophical debate, Śaṅkaracārya, however, was able to reestablish the prestige of the Vedic literatures such as the Upaniṣads and the Vedānta. Wherever Śaṅkaracārya traveled in India

he was victorious and opposing philosophies bowed. Śaṅkaracārya established his doctrine, Advaita–Vedānta, non-dualisitc Vedānta, by reconciling the philosophy of the Buddhists. He agreed with the Buddhist concept that corporal existence is unreal or asat – but he disagreed with their conception of prakṛti-nirvāṇa. Śaṅkaracārya presented Brahman, spiritual substance, as a positive alternative to the illusory plane of matter. His philosophy in a nutshell is contained in the verse brahma satyaṁ jagan–mithyā – ‘Brahman or spirit is truth, whereas jagat or the material world is false.’ In other words, Śaṅkaracārya’s philosophy was a compromise between theism and atheism. It is said that Śaṅkaracārya, according to the necessity of time, place and circumstance, took the position between theism and atheism because the wholesale conversion of Buddhists to the path of full-fledged theism would not have been possible.

Professors of philosophy in India refer to a verse from the Padma Purāṇa that reveals the hidden identity of Śaṅkaracārya: “The māyāvāda philosophy”, Śiva informed his wife Pārvatī, “’is covered Buddhism. In the form of a brāhmaṇa in the Kali-yuga I teach this imagined philosophy.” Śaṅkaracārya is thus widely accepted as an incarnation of Śiva.

In the small village of Kaladi, in the southern province of India, Śrī Śaṅkaracārya advented himself as the son of a Vedic brāhmaṇa named Śivaguru and his wife Ārya. Even in childhood it was apparent that Śaṅkara, as his father named him was a great personality. At his birth astrologers predicted that the boy would become a powerful scholar who would be like an elephant in a banana plantation in the matter of destroying false religions and spurious doctrines. As a student Śaṅkara quickly gained proficiency in the Sanskrit language. He had a prodigious memory; anything his teachers said stuck in his mind forever. What the average student learned in twelve years Śaṅkara learned in one.

When Śaṅkara was three years old his father passed away. Life was difficult for mother and son, but by the grace of God they lived peacefully according to their means. Śaṅkara continued his studies until his eighth year when he decided to take sannyāsa and live a life of renunciation. One day, Śaṅkara said to his mother, “The life of a man on earth is so full of misery that he sometimes wishes that he had never been born. The dullest among men knows that the body is destined to die at the appointed time. What the yogi alone knows is that in the cycle of saṁsāra one is born and dies again and again a million times. In the cycle of saṁsāra he sometimes plays the role of a son, a father, a husband, a daughter, a mother, or a wife in an unending succession. Therefore, true and lasting happiness can be achieved only by transcending birth and death through renunciation, which is the gateway to self-realisation. My dear mother, please permit me to embrace that state and strive to realise myself. Allow me to accept sannyāsa.”

“Don’t speak like that again,” replied his affectionate mother. “I wish to see you marry and become a good husband for a good woman. Please do not speak of taking sannyāsa again.”

A few days later while Śaṅkara was bathing in the river a crocodile caught hold of his leg. Seeing the hopeless position of her son the mother began to cry piteously. It appeared that the crocodile might devour her son alive. “Mother!” said the boy, “There may be a way that I can be saved. It is said by the wise men of our country that if one agrees to accept sannyāsa when one’s life is in danger, one will get out of that danger. Therefore, please permit me to renounce the world.”

Prepared to do anything to save the life of her son, the poor woman consented to his request. Śaṅkara then raised his hands and pronounced the words sannyāso’ham, “I have renounced.” When this was done the crocodile immediately let go of Śaṅkaracārya’s leg and his life was spared. As he come out of the water he and his mother embraced. “My dear mother, you have always been my provider. Now I am going out into the world and henceforth whoever feeds me is my mother, whoever teaches me is my father. My pupils are my children, peace is my bride, and solitude my bliss. Such are the rigors of my undertaking.”

“Be blessed my son. Your life is now in the care of the Supreme Benefactor.” With this heartfelt exchange between mother and son, Śaṅkara departed.

Wearing a simple cloth, carrying a little water in a pot, and traveling only on foot with a staff in his hand, the young Śaṅkara roamed across the countryside for many months. One day while resting in the shade of a banyan tree Śaṅkara noticed a few frogs sitting peacefully next to a cobra. Seeing this curious sight, he remembered the lessons of his previous teachers that coexistence between natural enemies was possible only in the vicinity of a great sage or an enlightened guru.

Upon inquiry from the people of the local village, Śaṅkara learned of a saintly person named Govindapāda who lived nearby in a cave. He decided to go there immediately. Offering prostrated obeisances in front of the cave Śaṅkara recited a delightful hymn in praise of the great guru. “My obeisances to you revered Govindapāda, who are the abode of all knowledge. Your fame has spread far and wide because you have traveled inward into yourself – to the very core of your being. You are the most realised person on earth, since you had the good fortune to become the disciple of Gauḍapāda, the disciple of Śukadeva, who was the self-realised son of Vyāsadeva, the compiler of Vedic literature. Thus you have a most remarkable line of spiritual preceptors. Please accept this unworthy sannyāsī as your disciple and make me heir to the knowledge of self-realisation.”

Govindapāda was pleased to accept this little sannyāsī as his disciple and he imparted the four sutras to him that Śaṅkara would later preach throughout the world:

prajñānam brahma – Brahman is pure consciousness

ayamātmā brahma – soul is Brahman

tat tvam asi – you are that consciousness

ahaṁ brahmāsmi – I am Brahman

Śaṅkara stayed with his guru for a long time, until one day Govindapāda, understanding that the young Śaṅkara was an incarnation of Lord Śiva, said, “Now listen to my wish. Proceed to the holy city of Banaras immediately and start instructing the people on how they can understand their real self. That which is taught by the Buddhist philosophers does not reveal the nature of the ātmā or self. It is your mission to bring the people to the path of theism. Banaras has many well-known scholars in all systems of philosophy. You must hold discussions with them and guide them along the lines of correct thinking. It is most urgent! Please do not delay even one minute.” Taking the order of his guru, Śaṅkara started for Banaras.

When Śaṅkara entered among the learned circles of Banaras he was barely twelve years old. Indeed, his tender age accompanied by his extensive knowledge and deep realisation astounded all who came to see him. As destined by providence Śaṅkara soon attracted many disciples who sat before him in rapt attention to his every word on transcendence. From that time onward Śaṅkara became known as Ācārya or Śaṅkaracārya.

At Banaras, Śaṅkaracārya turned the tide of atheism. He compiled commentaries on the Brahma-sūtra, Bhagavad-gītā, and the principle Upaniṣads, all of which explained the non-dual substance, Brahman, as the ultimate reality. Among his followers, his commentary on the Brahma-sūtra, known as Śāriraka–bhāṣya, is considered the most important. Śaṅkaracārya comments on the nature of Brahman as that which is beyond the senses, impersonal, formless, eternal, and unchangeable, as the summum-bonum of the Absolute Truth. According to Śaṅkaracārya, that which is known as the ātmā or soul is but a covered portion or illusioned portion of the Supreme Brahman. That illusion, says Śaṅkaracārya, is due to the veil of māyā, which is alone created out of ignorance or forgetfulness of the true self. The philosophy that the Absolute Truth can be covered by maya was later challenged successfully by Śrī Rāmānuja. Those who continue to follow the teaching of Śaṅkaracārya became known as Mayavadis, or philosophers of illusion.

Śaṅkaracārya’s theory of illusion states that although the Absolute Truth is never transformed, we think that it is transformed, which is an illusion. Śaṅkaracārya did not believe in the transformation of energy of the Absolute. Acceptance of the transformation of energy would have necessitated the acceptance of the Personality of the Absolute Truth or the personal existence of God – full-fledged theism. According to Śaṅkaracārya we ourselves are God. When the veil of ignorance is removed one will realise his complete identity as being non-different from the Supreme Brahman or God. Śaṅkaracārya held that the questions about the origin of the universe and the nature of illusion were unanswerable and inexplicable.

Śaṅkaracārya’s conviction was that the spiritual substance, Brahman, is supra-mundane, as well as separate from the gross and subtle bodies of mind and intelligence in this world. Śaṅkaracārya further stressed that mukti, or liberation from the cycle of birth and death, is possible only when the living being renounces his relationship with the material world. Śaṅkaracārya says that the concepts of ‘I’ and ‘Mine’ – I am this body, the centre of enjoyment, and these are my possessions: wife, children, property, etc.–are the causes of bondage to material existence and must be given up. Thus the bulk of his followers were and continue to be celibate students.

To support his conclusions of Advaita-Vedānta, non-dualism, Śaṅkaracārya interpreted the Vedas to suit his means. In other words, the Vedas have their direct and indirect meanings. Śaṅkaracārya, using grammatical jugglery of suffixes, prefixes and affixes, gave an imaginary or indirect interpretation of his own. Thus Śaṅkaracārya, positioning himself between the theist and the atheist, sometimes appears to have been the friend of both. It was indeed the method used by the great ācārya to lay the foundation for future theistic evolution. The contribution of Śaṅkaracārya in the development of theistic thought, from the atheistic or neo-theistic concepts of the Buddhists’ prakṛti-nirvāṇa to those of the sublime transcendental substantive Brahman, has made India and generations of future theists forever grateful.

Accompanied by a group of disciples Śaṅkaracārya traveled throughout India. To the north he traveled as far as the āśrama of Badarīnātha in the Himalayas. There he established a monastery for meditation and Vedic studies. Similar monasteries were established during his travels to Purī, in the east, Dvārakā in the west, and Śṛṅgeri in the south. All of these institutions established by Śaṅkaracārya still exist twelve centuries later.

On one of his journeys in southern India, Śaṅkaracārya chanced to debate with a famous scholar of Māhiṣmatī named Maṇḍana Miśra, ‘the jewel among scholars.’ Many learned persons gathered for the debate and Bhāratī, the good wife of the scholar, was chosen to be the judge and moderator. At the outset of the debate Bhāratī placed a garland of flowers around the neck of each of the two contestants. She proclaimed that at the end of the discussion whoever was wearing the garland which had not withered would be the winner.

Maṇḍana, who had never known defeat, opened the debate by stating, “I accept the authority of the Vedas. Their main teaching is that merit can be acquired by the performance of the prescribed rituals in the prescribed manner. One who performs these rituals will go to heaven and dwell in the company of Indra and the celestial damsels. When the merit is exhausted, he will return to earth so that he can acquire more merit for a longer stay in the world of the gods. The Vedas also contain related commandments as a prerequisite to the performance of the rites.”

The audience, consisting of many of Maṇḍana’s admirers and disciples, applauded his statement.

Śaṅkaracārya then responded, “I also accept the authority of the Vedas. Their main purpose, however, is this: Brahman alone is real; the phenomenal world is an illusion; and the individual soul is identical with Brahman. The parts of the Vedas containing descriptions and injunctions pertaining to ritual are subordinate to the major part that deals with the knowledge of the self and the ways of its acquisition. Rituals can only lead to karma – both good and bad, which prevents one from attaining self-realisation. The only goal of the Vedas is Brahman.”

Both scholars showed profound knowledge of the Vedas in various ways, and the discussion continued unabated for eighteen days. On the last day it was seen that the garland of Maṇḍana Miśra had begun to wither and the garland of Śaṅkaracārya remained ever-fresh. Bhāratī then declared Śaṅkaracārya the winner. Now Maṇḍana Miśra would have to renounce his connection with the world and become the disciple of Śaṅkaracārya.

In a final attempt to save her husband, Bhāratī said, “Oh Great ācārya, you are certainly victorious in the debate with my husband and he will have to become your disciple. However, I, the wife of Maṇḍana Miśra, am his better half. Before your victory is complete you will have to defeat me also.” Śaṅkaracārya was somewhat surprised, but he accepted the challenge.

Addressing Śaṅkaracārya, Bhāratī said, “I cannot admit that you are the master of all learning unless you can prove that you have a good understanding of sex education also. Now, tell me, what are the various forms and expressions of love? What is the nature of sexual love? What is the effect of the waxing and waning moons on sex urge in men and women? You must answer all these questions.”

Being a celibate monk and only sixteen years old, it appeared as though Śaṅkaracārya had been bewildered by his opponent. He then asked for forty-days additional time since he was not prepared to speak on the subject immediately. Bhāratī granted the request and Śaṅkaracārya and his disciples left the assembly. Through the powers of mystic yoga Śaṅkaracārya experienced erotic love and acquired knowledge of all its intricacies. Before the forty days had ended Śaṅkaracārya re-entered his own body and returned to debate with Bhāratī.

After a brief discussion, Bhāratī conceded that Śaṅkaracārya was the undisputed winner. Śaṅkaracārya was now the leading spiritual master in India. Day and night for sixteen continuous years Śaṅkaracārya preached the Advaita Vedānta. In his thirty-second year while on pilgrimage in the Himalayas, Śaṅkaracārya left this mortal world for the eternal abode.

During his life Śaṅkaracārya had composed a number of beautiful verses known as Bhaja Govindam “Worship Govinda.” A mystery surrounds these prayers in that Śaṅkaracārya taught consistently throughout his commentaries that Brahman is the supreme goal. Yet in his prayers he says, “Just worship Govinda.” Many commentators on the life of Śaṅkaracārya consider that his being an incarnation of Śiva means that Śaṅkaracārya was in fact the greatest devotee of Godhead, but due to the necessity of the time he could not directly advocate devotion as the highest attainment.

Before departing from this world Śrī Śaṅkaracārya spoke these last words:

bhaja govindaṁ bhaja govindaṁ bhaja govindam mūḍha-mate

samprāpte sannihite kāle na hi na hi rakṣati ḍukṛṇ-karaṇe

“Worship Govinda, worship Govinda, Oh you fools and rascals, just worship Govinda. Your rules of grammar and word jugglery will not help you at the time of death.”

More Articles by Swami B.G. Narasingha

The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus Christ

The article, “The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus Christ” was written by Śrīla Narasiṅgha Mahārāja under the pseudonym of ‘Pradeep Sharma’ in 2007. This article was in response to various parties begging the question about Jesus being a devotee of Kṛṣṇa and citing a dubious work called the ‘Aquarian Gospel’ as evidence.

Meditation Techniques and the Holy Name

'Meditation Techniques and the Holy Name' was written by Swami Narasingha in October 2006. Narasingha Maharaja discusses the age-old problem of distraction during japa, and gives advice based upon Sanātana Gosvāmī and Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura on how to combat this.

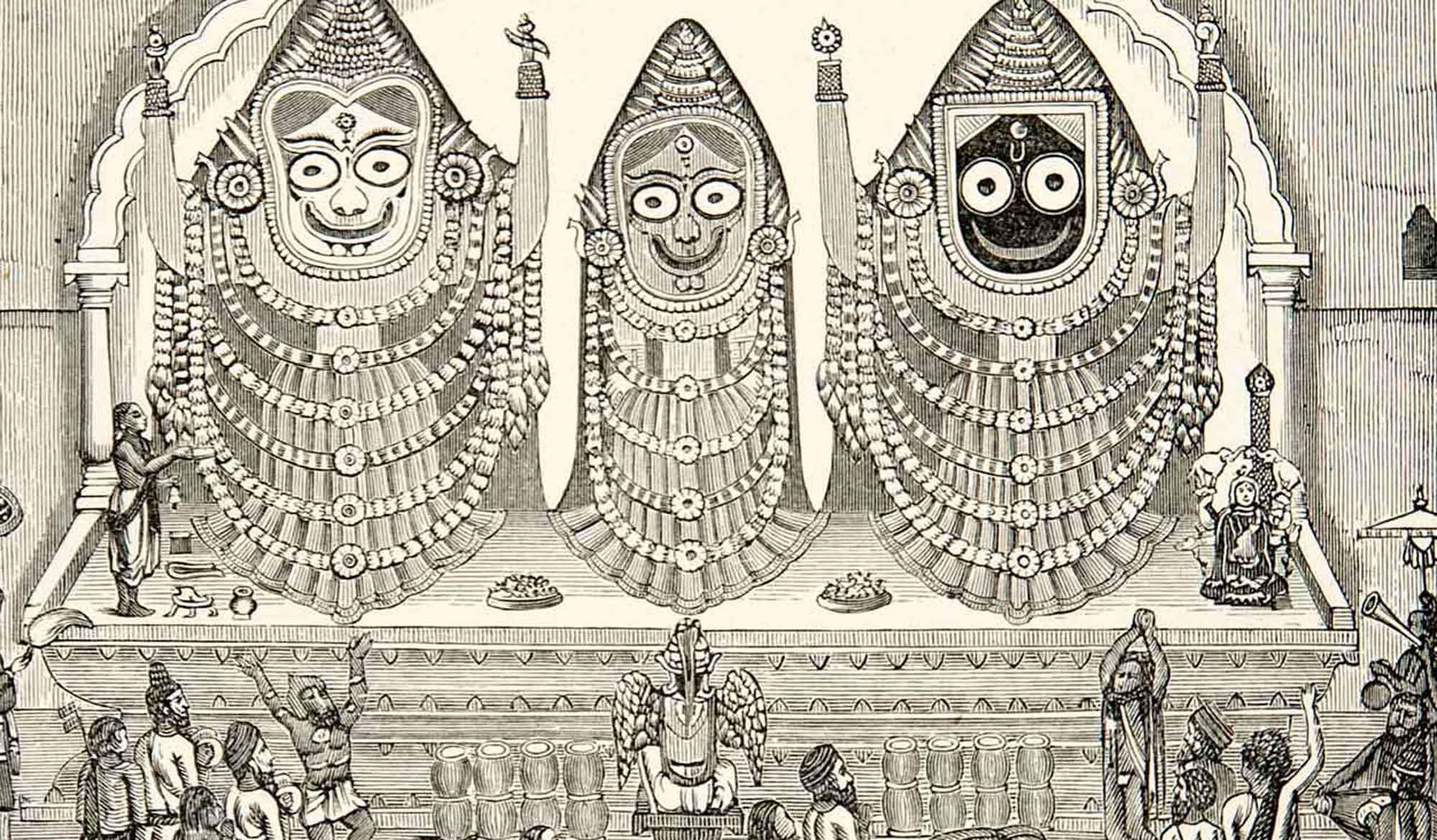

The Burning Cross – Part 2

In ‘The Burning Cross - Part 2’, Śrīla Narasiṅgha Mahārāja, under the pen name of Pradeep Sharma, discusses the Goan Inquisition, how the Christians viewed Lord Jagannātha in Purī, and the thoughts of the Founding Fathers of the Unites States about Christianity.