Ācārya Siṁha

The Life of Swami Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

Chapter 2 – Escaping Conformity & The American Counterculture

(1960-1966)

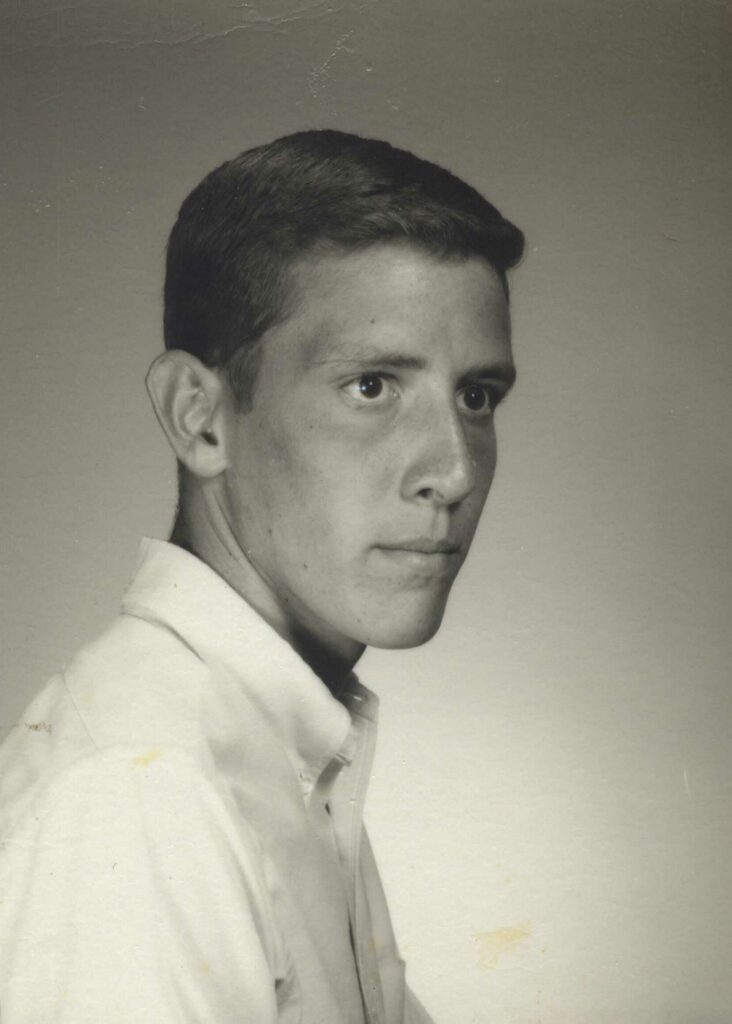

To say that Narasiṅgha Mahārāja’s relationship with his father had never been good would be an understatement. When Mahārāja did excel at a subject or sport at school, his father would simply ridicule him and stifle any enthusiasm. Like most boys of his age, Mahārāja was sometimes mischievous, but the punishments his father meted out were often extreme.

The relationship with his father became so strained, that in 1960 when he was 14, his mother sent him off to Cumberland, Maryland, to live with his maternal grandmother, Grandma Tressler. There, he went to Allegany High School where his history teacher made an unusual and accurate prediction.

The teacher had nicknamed him ‘The Nomad’ because during class he was in the habit of gravitating from one seat to another. One day the teacher began speaking about all the pupils individually and predicting what each one of them would do in the future. When he finally got to ‘The Nomad’ he said that he would be a teacher – he would roam around with no fixed place and teach many people.

Narasiṅgha Mahārāja had been happy staying with his grandmother and only reluctantly returned home when he was 17 because his dying paternal grandmother had made him promise to do so. He had hoped that things at home would be better than when he left, but it was, in Mahārāja’s own words, “business as usual.”

He was enrolled in Nathan Bedford Forrest High School in Jacksonville, Florida (an institution dubiously named after a famous Confederate general and the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan), enduring the same academic torpor he always experienced at school. When junior Prom Night came around, the whole school was abuzz, but Mahārāja saw it for what it was – shallow and banal. He showed no interest whatsoever and while his fellow students were busy preening themselves, Mahārāja spent the entire evening at the basketball court.

He was enrolled in Nathan Bedford Forrest High School in Jacksonville, Florida (an institution dubiously named after a famous Confederate general and the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan), enduring the same academic torpor he always experienced at school. When junior Prom Night came around, the whole school was abuzz, but Mahārāja saw it for what it was – shallow and banal. He showed no interest whatsoever and while his fellow students were busy preening themselves, Mahārāja spent the entire evening at the basketball court.

Narasiṅgha Mahārāja: I was alone playing basketball, when my friend Crip pulled up in a rented sports car convertible, wearing a white tuxedo with a red carnation. He decided to play a little basketball before going to the Prom, so he put his jacket on the seat of the sports car and we did a couple of moves. At one point, the ball went up, and we both jumped up to catch it. Well, what goes up must come down! He had this habit of sticking his tongue out. He was above me, and I was coming up. His chin hit the top of my head, which pushed his teeth forward and cut off the end of his tongue. It was just hanging there, on a piece of skin. Blood gushed everywhere – all over his white pants, white shoes. His whole prom night outfit…blood red! Then he just pushed the thing back in his mouth, jumped in his car, started it, and drove off.

As mentioned previously, Mahārāja was apathetic when it came to mundane academics. With the exception of history, he found all the subjects taught at school to be tediously repetitious and unengaging. Suffice to say, when it was time for exams he didn’t fare so well. Taking pity on him, his carpentry teacher told him that he would award him the marks necessary to graduate if he made something ‘passable’ in woodwork. Mahārāja spent a whole day making a varnished wooden bowl and his teacher eventually granted him a C+ – just enough for a passing grade.

Finally, graduation day arrived. Upon receiving his diploma, Narasiṅgha Mahārāja went home and promptly threw it in the trash. Even back then, he considered the whole mundane educational system to be practically useless. He figured that having a high school diploma was not worth much (unless one planned to work in the post office).

The summer after graduation in 1964 had not been especially productive for Mahārāja. With no plans for college, he had gotten a part time job at a furniture factory working for minimum wage, spent hours doing lawn chores in the sweltering Florida heat, sat in his room listening to his mother and father arguing with each other, and munched on overly-sugared Cheerios while reluctantly babysitting and changing the diapers of his three siblings while his parents went out with friends.

Then, on August 24th 1964, the day after Mahārāja’s 18th Birthday, his father walked into his bedroom and delivered an ultimatum. “Son, you can either join the military service of your choice or leave my house!”

“Yes sir,” his son replied.

Mahārāja immediately felt a huge surge of relief and euphoria. No sooner did he hear the sound of his father’s footsteps stomping away towards the master bedroom, he threw some clothes into a gym bag, stealthily opened his door, slipped down the stairs and bolted across the living room to the front door. Looking back for a moment, he saw the tearful face of his mother. She knew he was leaving for good. He wouldn’t see his parents again for another 26 years.

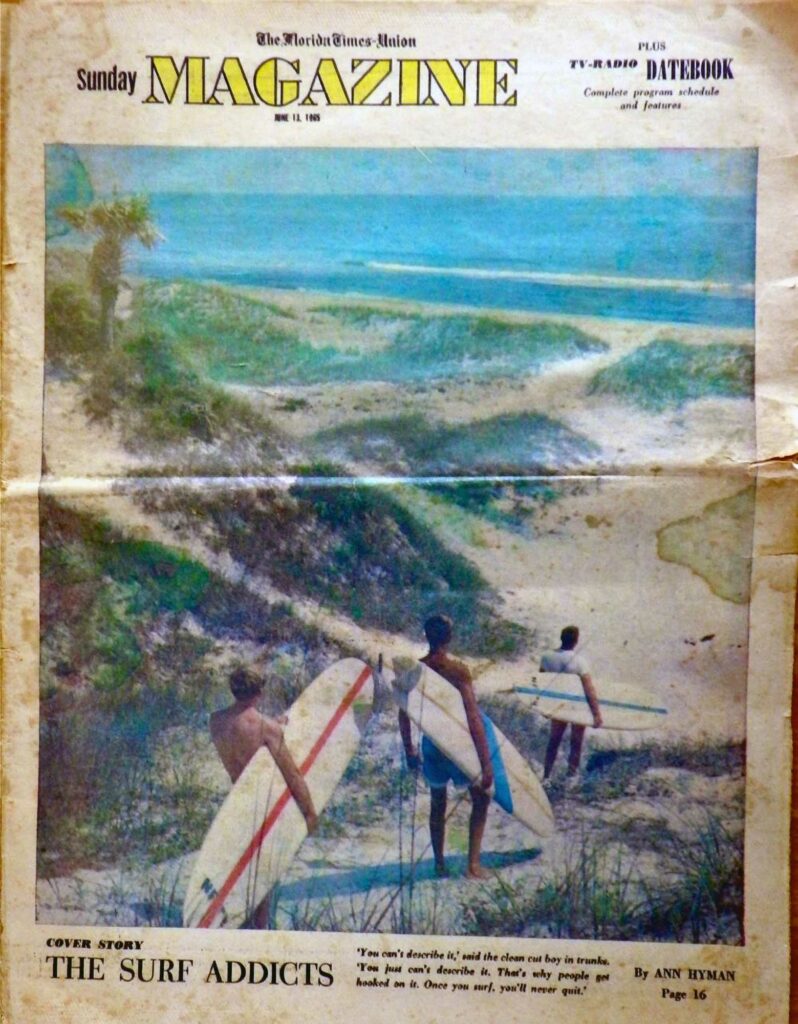

The first night away from home, Narasiṅgha Mahārāja stayed at a friend’s house and in the morning, he hitchhiked to the beach. Mahārāja had begun surfing the summer before while spending the weekend at the beach with his family. He saw surfers for the first time and rented a surfboard for an hour or so. He immediately caught the ‘surf-bug’ and it wasn’t long before he bought his own surfboard. He usually kept his surfboard at the house of his friend Bill Perry on 1st Street near the pier. Bill’s mom was a favourite with all the surfers who kept all their boards (as many as 25 at any given time) at her house. Even when Mahārāja and his friends were sunburned to a crisp, totally exhausted from hours in the surf and absolutely starving, Mrs. Perry would make them peanut butter & jelly sandwiches and sometimes peach cobbler. During that period, Mahārāja mostly lived on the beach, giving some surf lessons to tourists for $2 an hour and hanging out with friends.

Surfing was still in it’s infancy in the U.S., with only a few hundred participants countrywide. Thus it was no surprise that in June 1965, Mahārāja and his friends made it on the front cover of the Florida Times Union Sunday magazine.

(Times Union, Sunday insert magazine printed in June 1965. Narasiṅgha Mahārāja is in the centre)

(Times Union, Sunday insert magazine printed in June 1965. Narasiṅgha Mahārāja is in the centre)

Reality set in when the tourist season ended and Narasiṅgha Mahārāja realised that he needed to get some form of employment in order to maintain himself. After a few short-lived jobs, Mahārāja eventually began work at a surf shop, repairing surfboards. It was a dream-job for a surfer. Mahārāja and his friends eventually pooled their money together and rented a two-story house on the beach near Jacksonville Pier for $80 a month.

Narasiṅgha Mahārāja: I knew I could do that, and I liked doing that. So that’s what I did – I went surfing, and fixed surfboards. I didn’t really crank out a real high level existence. We were gonna dig a cave underneath the surf shop and live down there, but then we rented a house instead.

During this period, for the second time in his life, Narasiṅgha Mahārāja saved someone from drowning.

Narasiṅgha Mahārāja: This fat old lady was in the ocean right in front of the surf break – she was gonna get smashed on the rocks. So I paddled over, dragged her onto my boogie board, and took this ‘walrus’ through the water, all the way around to where the tourists swim. She was about 58 years old, but looked as if she was 98. Then her husband came. I figured they were from some eastern European country because of their heavy accent. The lady said, “Oh, you save my life! I buy you steak dinner.” I was thinking, “Hey, a hundred bucks would be better!”

Just when things seemed to be looking up, the war in Vietnam began to escalate. All men in the United States of draft age (between 18-25 years) had to register with the U.S. Selective Service System within 30 days of their 18th birthday. Narasiṅgha Mahārāja and most of his friends came from military families and were already sick and tired of that lifestyle – as far as they were concerned, they’d already done their time in the military. Compounded with this was the fact that none of them really wanted to be sent to some unknown Asian country thousands of miles away to fight an unnecessary war, only to be shipped back home in a body bag. However, Ricky Luce, one of Mahārāja’s surfer friends did enlist in the army but never saw active duty in Vietnam – a few weeks into basic training he was killed by a grenade explosion. Upon attending his friend’s funeral, Mahārāja became determined not to follow in his footsteps or fight in a war that wasn’t worth dying for.

The Vietnam War was arguably one of the most important factors contributing to the rise of the counter-culture movement of the 1960s, and, like many young people at that time, Mahārāja became part of that phenomena. Like most of the youth of the United States at that time, he felt frustrated with the establishment. At the same time however, he didn’t even know who the president was – he had little to no interest in politics, never read newspapers, and never listened to the news on the radio or T.V.

Narasiṅgha Mahārāja: The counter-culture generation of the 60’s wanted change from the otherwise stereotypical lifestyles of the previous generation. The goals were to end the war in Vietnam, spread the use of psychedelic drugs as consciousness-uplifting sacraments, achieve equal social and civil rights for all and question the materialism that prevailed in the country.

Post World War II was a time of conformity in America. Americans were expected to have a job, a house, a family and a car. Conformity was the American way of life. In the eyes of the hippie movement, America had become a nation obsessed with brands and maintaining the status quo. Their greatest social concerns were shaved legs, good breath and deodorant. But here was a generation that wanted change – to reject that way of life and redefine one for themselves.

As far as mainstream religions were concerned, most young Americans rejected them, considering them to be shallow and hypocritical. On one hand they spoke so much about loving thy fellow man, but their leaders and priests promoted the Vietnam War and turned a blind eye to racism against the black community at home. The youth of America were in favour of embracing more unconventional beliefs that led to personal spiritual experiences. Many eastern religions became very popular at the time because they taught that an individual could work towards spirituality and enlightenment, without a priest telling them what to do.

Narasiṅgha Mahārāja: I was always seen as being, not just a spiritual person, but a preacher, even around the hippies. Not in a big sense – there were some big hippy gurus such as Timothy Leary, Allen Ginsberg and Ken Kesey. I was nothing like them, nor did I ever have any interest in that kind of world. My ‘preaching’ was just amongst my friends. But at the time, we were in total darkness. As far as eastern mysticism was concerned, there was nothing around except Baba Ram Dass and a few hokey sounds coming out of India. There was Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi and The Tibetan Book of the Dead…so if you tried putting it together from all that, you didn’t have a chance! But when Śrīla Prabhupāda came, it was like the parting of the Red Sea!

One night, Mahārāja had a vivid dream where he saw a piece of meat sizzling in a frying pan on a stove. As he stood watching the burning flesh, it began to breath, scream and ooze blood as if it were alive. He woke up with a jolt. This dream left such an impression on him that he was determined to become a vegetarian and never ate meat again for the rest of his life.

During this time, Mahārāja visited Mexico where he came in contact with yoga for the first time:

Narasiṅgha Mahārāja: We were surfing a break north of Puerto Vallarta (on La Punta), and when I came out of the water after an evening session, there was this guy sitting up on the rocks in a yoga posture. To us, he looked a bit twisted up, like deformed or something. We had never seen anything like that until then. We were not very experienced in anything other than surfing. Someone pointed this guy out and made a joke at his expense and we all laughed aloud. As we packed up our gear, I noticed that this guy was walking away down the beach. Curiosity got the better of me and I walked quickly until I caught up to him. We talked and he said he had just come from India. At that stage in my life I didn’t even know where India was, much less know anything about Indian culture or spirituality. I rather boldly blurted out, “What were you doing on the rocks?” His response was that he was “Reaching for eternity.” To me this was weird, but provocative, so I questioned him further, “What do you mean?”

“Everything everywhere is made of energy” he replied, “And that energy has an eternal source — find it and you have reached eternity.”

This certainly didn’t make a whole lot of sense to me, but his words pierced deeper than any I had ever heard before. My friends started honking the horn and it was time to go. This guy on the beach had met a guru in India who taught him yoga, and he was now traveling the world in search of enlightenment. This very much appealed to me. After that one brief chance meeting, I never saw that person again. But something clicked in me and my path was set. From then on, being in the ocean or anywhere for that matter, I felt like a particle of dust floating in an infinite ocean of energy, and the desire to know where it all came from grew and grew in me. It was something that didn’t go away. It stuck.

(Haight-Ashbury, San Fransisco 1966)

(Haight-Ashbury, San Fransisco 1966)

In 1967 Narasiṅgha Mahārāja decided to go to Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco, the heartland of the hippie movement. Taking a $10 flight from San Diego, he made his way to Golden Gate Park and spent his first night sleeping under a bush. After a few days, he met a couple of hippies named Buddy and his girlfriend Robin who invited him to stay with them in their apartment on Fredrick Street.

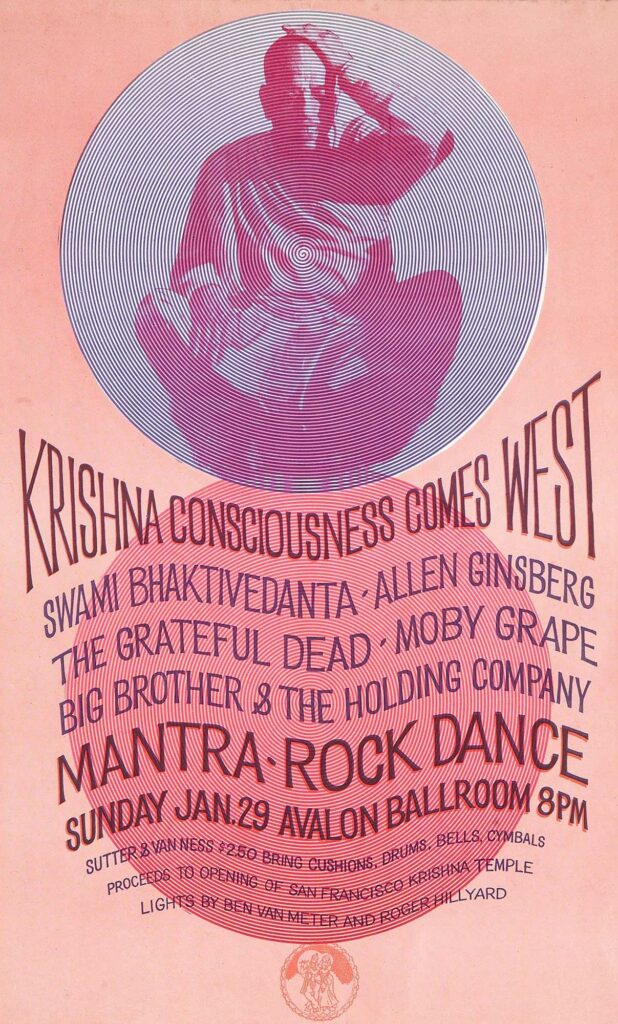

Some nights Mahāraja would go to the Avalon Ballroom or The Fillmore where the best bands played. Then one evening he saw a brightly coloured poster at the Avalon advertising a Mantra-Rock Dance. The poster read:

Krishna Consciousness Comes West

Swami Bhaktivedanta – Allen Ginsberg

The Grateful Dead – Moby Grape

Big Brother and the Holding Company

Mantra-Rock Dance

Sunday… Avalon Ballroom 8pm

He was very eager to see a real swami from India and hear some of his favourite bands, so he headed over to the Avalon that Sunday. However, there was no Swami Bhaktivedanta, no Allen Ginsberg and no Moby Grape – Mahārāja had failed to notice that the poster was for Sunday, January 29th. It was June…he was five months too late!

Not long after this, on a Sunday afternoon on what was popularly called ‘Hippy Hill’ in Golden Gate Park, Narasiṅgha Mahārāja saw a group of people clad in saffron robes, chanting, dancing and handing out sweets that they called ‘prasādam’. He sat and watched them for a while, then joined in with the chanting. After the chanting had stopped, one of the members spoke something about ‘spiritual planets’ and how the denizens of those planets had ‘spiritual bodies.’ Mahārāja thought this sounded amazing. This was his first encounter with the Hare Kṛṣṇa Movement!

(Devotees dancing at Hippy-hill in Golden Gate Park, San Fransisco circa 1967)

(Devotees dancing at Hippy-hill in Golden Gate Park, San Fransisco circa 1967)

Narasiṅgha Mahārāja: The Hare Kṛṣṇa’s were super popular in those days. In fact, they were friends with all the big bands at the time – Big Brother, Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead – because they fed people in the park and at their temple where you could always get a meal. The first prasādam I was given was from a girl dressed in a sari, a brahmacārinī. She was preaching to another long-haired guy, who was really tall, about the spiritual world. He was so high that he was probably trying to figure out what planet she was from! Anyway, she was passing out round sweet-balls from a big baking tray – ‘Simply Wonderfuls.’ It was sugar and butter, with a little powdered milk to make it stick together. So I ate this thing and as soon as I bit into it, I was in bliss! My eyes rolled to the back of my head! I’d never tasted anything like it. It was butter and sugar combined – plus, it was prasādam! Then, while she was busy preaching to this hippy, I reached over and I took another one! I remember that the brahmacārinī was telling this hippy, “In the spiritual world, everyone has a spiritual body” and when I heard that, I was like, “Wow!”

After that, I ended up going to the zoo that morning and I was looking through the fence at some American buffalo. I had never been up close to one of them before – they looked gnarly, almost prehistoric! I still remembered what the girl in the park had said about ‘spiritual bodies’ and I was confused. I was looking at this buffalo and thinking, “A spiritual body like that??” I didn’t understand that you are a soul and the soul resides inside the body and eventually leaves it. I had no idea how you got a body in the first place.

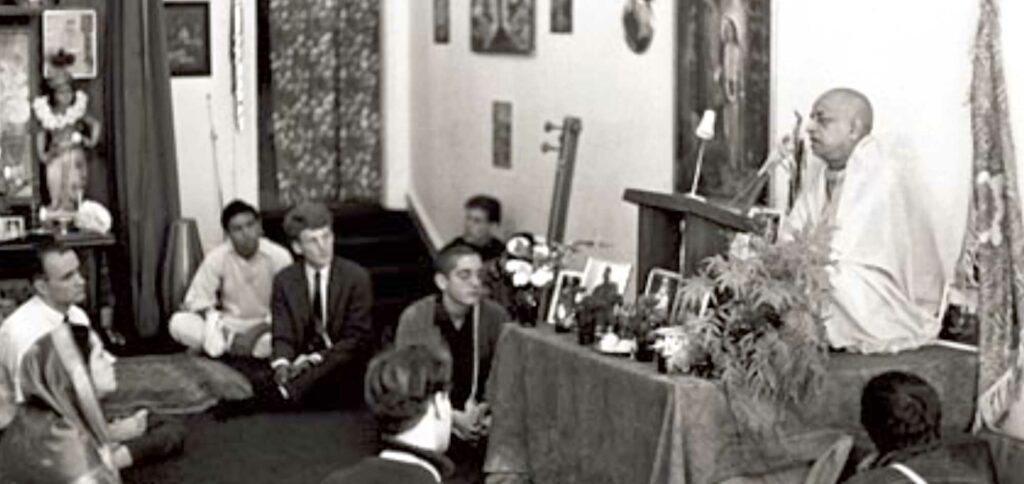

That same afternoon as he was on his way back to the apartment on Fredrick Street, he came across a doorway which was spilling over with shoes. From the inside came the sound of bells, drums, loud chanting and the exotic smell of incense. He immediately recognised the chanting as the same he had heard in the park earlier that day:

(Śrīla Prabhupāda at the Fredrick Street Temple in San Francisco)

hare kṛṣṇa! hare kṛṣṇa!

kṛṣṇa kṛṣṇa! hare hare!

hare rāma! hare rāma!

rāma rāma! hare hare!

Entering the building, Mahārāja found himself standing inside a Kṛṣṇa temple for the very first time. Since it was so crowded, there was standing room only. There was an intense mood in the room as everybody chanted at the top of their voices, jumping up and down, banging drums, tambourines and a medley of other musical instruments. Despite being the tallest man in the room, Mahārāja could still not see past the many swaying heads and upraised arms as to who or what they were focused on. As he looked around the room he saw a life-size painting on the wall of an unfamiliar Indian guru – a regal looking swami, shaven-headed, dressed in orange robes with a bag on his hand. After getting his feet stepped on several times and getting constantly pushed back to the doorway by the thronging crowd, Mahārāja finally left the temple and continued on to his apartment.

That day, Mahārāja had accepted prasādam, chanted the mahā-mantra and, unbeknownst to him, had come within a few feet of Śrīla A.C. Bhaktivedānta Swami Prabhupāda, who would later become his spiritual master.

However, the extraordinary events of that day were suddenly eclipsed when he returned to his apartment. As he approached, he saw medics carrying a body covered with a white sheet on a stretcher into an ambulance. Bewildered, Mahārāja stood there watching, and after the ambulance had pulled away, he entered the apartment and found everyone in a state of shock and confusion. Robin, Buddy’s girlfriend, had overdosed on heroin and died. Mahārāja had no idea she was even taking heroin. He had developed a strong brotherly bond with Buddy and Robin, but now Robin was gone forever and Buddy was nowhere to be seen.

Despite the presence of so many peace-loving hippies, violence was also on the rise in San Francisco. His witnessing a seven year old girl and her mother getting mugged and beaten in broad daylight as well as Robin’s death was the catalyst for Mahārāja to leave Haight-Ashbury. He decided to go to the Morning Star commune in Sonoma County for a while.

Before leaving the Haight however, Mahārāja knew that sooner or later, the Selective Services Department would be searching for him in order to draft him into the army. Therefore he created a false ID card under the name of ‘Jack Lyin.’

Narasiṅgha Mahārāja: Back then you could just make these things with Letraset. It was common that the police would stop young people randomly and ask for some form of identity. So they would look at my ID and ask, “Are you Jack Lyin?” and I’d say, “Yes sir, that’s me. I’m Lyin!” I thought it was hilarious, because I was ‘lyin’ (lying).

Eventually Mahārāja came up with a scheme. He left a fake suicide note in his apartment stating that he was planning to drown himself in the ocean. He hoped that this ruse would mislead the authorities and they would abandon their attempts to make him cannon-fodder in Vietnam.

Narasiṅgha Mahārāja: Somehow I faked a letter. In those days, you didn’t have the same information you have today to stay on top of things. If something was printed in the newspaper, that was big. That was evidence of something! Nowadays you can print anything in a newspaper, but back then, people believed what they read in the newspapers. Somehow or other, I faked the news of my death – it wasn’t in the newspaper, but it was through letters because the Military Police were going to come and I was registered at a certain address at the beach where all the guys lived. So we faked the message that I had died, so that if the Military Police came to my residence, they would tell them, “He went to California – he died a month or so ago.”

News of his ‘death’ eventually reached Jacksonville Beach, Florida, where his old friends were mortified. To mourn their old buddy they held a memorial service on the beach one night.

Narasiṅgha Mahārāja: We couldn’t tell anyone the plan. So when the others heard that I had died they were all shocked, and then a few months later, I came back to Jacksonville! Everyone was really upset! But they had to be tricked to be part of the scam.